By David Steers

The purpose of this paper is to give some explanation to the First Subscription controversy of the early eighteenth century. A number of people have asked me questions about our historical development so in this paper and some subsequent ones I will try and explain the story of what was eventually to become the Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church of Ireland. We have to begin with some basic definitions.

Presbyterianism basically means the organising of the church through presbyteries; that is a gathering of ministers and elders. It does not necessarily imply any particular doctrinal beliefs but has always been most closely connected, in most people’s minds in the English speaking world at least, with the form of church government and belief that developed in Scotland after the reformation, with the government of the Church by General Assembly, Synods, Presbyteries and Kirk Sessions.

Presbyterianism actually begins in Ireland in 1642. In that year the Scots army of General Munro established the first presbytery at Carrickfergus, although a few places had Presbyterian ministers in their locality decades before that. But the first presbytery was established during the turmoil of the civil wars and in the decades afterwards Irish Presbyterians struggled against civil and political disabilities throughout the seventeenth century and on into the eighteenth century. They maintained, however, close links with the Church of Scotland, regarding themselves as the daughter church of Scottish Presbyterianism, and were connected in many ways. A great many of the ministers in Ireland at the end of the seventeenth century were Scottish born and the vast majority of the new ministers who came forward in the eighteenth century were trained at Universities in Scotland, most especially at Glasgow. But while Presbyterianism was officially established in Scotland from 1690 onwards this was not the case in Ireland. Here Presbyterians were dissenters from the established church, from the Episcopalian Church of Ireland, in fact they were the first organised dissenting church in the British Isles. Undoubtedly too the re-emergence of Presbyterianism in its established form in Scotland after the Williamite Revolution of 1688-9 encouraged the Irish to organise themselves and the direct result of this was the first meeting of the Synod of Ulster on 30 September 1691.

So, very briefly, this is something of the background of Irish Presbyterianism at least in Ulster. In the South of Ireland the church developed a looser form that was influenced also by Presbyterianism in England and Independent churches in Dublin.

But before we proceed to look at the controversies that troubled Presbyterians in Ireland we should be clear about some of the terms we will use. Presbyterians in 1691 would have defined themselves, in religious terms, as Calvinists, that is followers of the sixteenth century French-born reformer John Calvin who led the reformation in the city of Geneva, one of the pivotal figures of the European reformation. The theology he formulated was one developed at a time of great turmoil in Europe and it needed to be sharp and robust to survive. Some, in later times, have seen it as narrow and harsh, concentrating too much on the image of God as a stern, unforgiving lawgiver, and certainly part of the struggles that developed within Irish Presbyterianism were to reflect different perceptions of the nature of God and a growing challenge to the Calvinism of the early years.

Alexander Gordon was a leading Non-Subscribing Presbyterian/Unitarian minister at the end of the nineteenth and start of the twentieth centuries. He was also a notable historian and remains, to this day, one of the most important historians of religious dissent in the British Isles. But his description of Calvinism and the controversy that surrounded it might be helpful. He wrote in the 1920s that “The first great stride of common advance was that from Calvinism with its Gospel of God’s love for the elect, to Arminianism with its Gospel of God’s love for the world at large.”

Arminianism here is a reference to people who were followers of the Dutch theologian Jacobus Arminius and many of the non-subscribers in the eighteenth century were to follow in his example of softening the harshness of traditional Calvinist doctrine.

What do we mean by subscription?

Well this is the key question and, of course, the document that needed to be subscribed to was the Westminster Confession of Faith. Put briefly this document is the standard expression of theological belief in the reformed tradition. Throughout Christian history theologians, church leaders and church councils have attempted to codify the faith, have attempted to wrap up all that is thought to be essential to be believed in by the faithful church member. Sometimes they have punished those who have not been willing to give their assent to these documents. Other times they have excluded those who have not accepted the document. The Westminster Confession emerged two years after the establishment of the first presbytery in Ireland in 1642. Amongst the many upheavals that occurred in the period of the civil war and the establishment of the rule of Oliver Cromwell as the Lord Protector one important event was the gathering of divines – that is ministers and theologians – in Westminster to produce a definitive statement of faith for the reformed churches. They were brought together in an Assembly to provide a Confession of Faith as well as doctrinal and liturgical standards for the Presbyterian system.

Within Irish Presbyterianism the status of the Westminster Confession became the centre of the argument between two points of view – one that stressed the idea of religious freedom and the rights of the individual conscience, and one that wanted to safeguard orthodoxy and prevent what they saw as theological error. This was an argument that developed gradually and was prompted by a number of factors.

The roots of the first subscription controversy lie at the start of the eighteenth century when an issue arose in Dublin that unsettled the peaceful life of the Presbyterian church. The Rev Thomas Emlyn was found to be what was termed an Arian in theology.

Arianism was a constant bogeyman for early eighteenth-century dissenters, particularly after the publication of Samuel Clarke’s Scripture Doctrine of the Trinity in 1712. Arianism was a form of theological belief which challenged the traditional formulation of the doctrine of the trinity, giving Jesus an exalted place but not as co-equal with the Father. Undoubtedly this view was present within the dissenting community but the fear of it often exaggerated the reality. Thomas Emlyn, however, certainly did promote Arianism but was heavily punished for having done so. He returned from England and received an enormous fine of £1,000, being imprisoned until he paid it. Subsequently Emlyn returned to London and established his own Arian congregation. But Emlyn founded no theological party in Ireland, his importance lies in the reaction he produced within the Synod of Ulster.

In 1705 the General Synod introduced a new rule that required all ministers to subscribe to the Westminster Confession of Faith at ordination. In part this was a response to the situation regarding Thomas Emlyn and reflected a desire to prevent the appearance of any further heresy. But it also followed the practice of the Church of Scotland which had gradually introduced stricter terms of subscription. At first there were no questions raised about this process in Ireland but this was soon to change and was brought about by a number of factors, but at the centre of them was a group of ministers who were members of a body known as the Belfast Society.

The Belfast Society

The Belfast Society began in 1705, the same year that subscription was introduced, but although it attracted much hostile criticism after the storm broke over the question of subscription, criticism which was often repeated and increased by later historians, its origins were not marked by controversy. It was a gathering not only of ministers but also of students for the ministry and some laypeople who met to study the Bible and discuss issues of theology and church practice together. At each meeting two members were appointed to study a certain passage of the Old and New Testaments and give a paper on their understanding of the passage.

What seems clear is that the template for this Society came from the experience of many of the members as students at Glasgow University. During the Professorship of James Wodrow, and under his more controversial successor John Simson at Glasgow, students were encouraged to meet together in just this way for informal discussion and consideration of the Scriptures. Particularly involved with the Belfast Society from the start were two of the most able ministers – who had both studied at Glasgow – John Abernethy and James Kirkpatrick.

In his account of the life of John Abernethy, often called ‘the father of non-subscription’ his friend and predecessor as minister in Antrim, James Duchal, whilst observing that “no man contributed more to the true ends” of the Belfast Society, also noted that James Kirkpatrick had been “greatly useful” to the Society. It seems very likely that to a large degree men like Kirkpatrick simply replicated the practices they had learned at Glasgow amongst his brethren in Ireland. Nevertheless writing some years after the controversies Duchal could say of the members of the Belfast Society that they were bringing “things to the test of reason and scripture, without a servile regard to any human authority.”

This is a key phrase, this idea of bringing things to the test, not only of scripture, but also of reason, and to do so without regard for human authority. It is clear that over time, under the leadership of Abernethy and Kirkpatrick, the Belfast Society became more concerned to explore more controversial questions of authority.

Partly as a result of their education in Glasgow which in turn gave them an awareness of wider Continental theological scholarship and partly because of an awareness of similar issues being raised in England by both dissenters and Benjamin Hoadly, a bishop of the Church of England, members of the Belfast Society – many of the most able ministers in Ireland – began to question subscription as part of a growing consideration of the nature of religious authority.

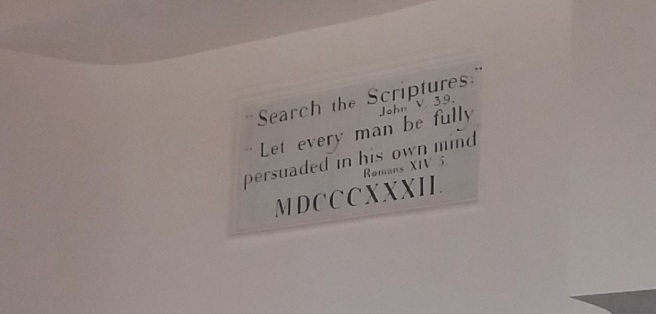

“Let every man be fully persuaded in his own mind.”

Matters came to a head in 1719 when John Abernethy preached a sermon before the Belfast Society on Romans ch.14 v.5 – “Let every man be fully persuaded in his own mind.” This sermon was strongly influenced by the ideas of Bishop Benjamin Hoadly who had preached before King George I two years earlier the idea that Christ sanctioned no visible Church authority.

Foundation stone of the former Remonstrant meeting-house, Ballymoney

Abernethy entitled his sermon Religious Obedience founded on Personal Persuasion and it was to plunge Irish Presbyterianism into a struggle that was to last for seven years and end with the expulsion of the liberal wing of the church. The sermon was published in 1720 and it immediately caused a storm. Abernethy took his stand on the sufficiency of scripture but with it the right of private judgement and the individual’s responsibility to employ the God-given faculty of reason in their religious opinions.

Abernethy argued that it was the Christian’s duty to examine all the evidence carefully and to act it on the basis of their own conscientious conviction. He and his supporters saw themselves as following very directly in the reformation tradition by emphasing the right of each individual believer to search the scriptures for themselves.

So with this emphasis on individual decision went an increasing questioning of the place of creedal formularies and with them the authority of the ecclesiastical bodies that upheld them. For presbyterians it meant that the traditional criticisms that they had directed at the Papacy and episcopalian churches were now being directed at their own synods and the Westminster Confession of Faith.

The whole matter rapidly moved from being a theoretical and theological discussion to one of direct practical import with the installation in Belfast of the Rev Samuel Haliday. On 28 July 1720 the presbytery of Belfast assembled at the meeting house of the first congregation to install the new minister. However, Haliday refused to subscribe the Westminster Confession in any form and instead substituted his own declaration. Four members of the presbytery objected to Haliday’s installation but under James Kirkpatrick’s direction the event went ahead. What is usually referred to by historians as the first subscription controversy was now underway.

At the Synod of June 1721 held in Belfast Haliday was again asked to give his assent to the Westminster Confession but again he refused.

The Synod went on to declare its allegiance to the Westminster Confession, a minority recording their protest at this move. In addition a split appeared within Haliday’s own congregation and a group petitioned the Synod to be allowed to leave and form a separate congregation.

A number of congregations were troubled by splits at this point. As well as the first church in Belfast, congregations such as Holywood and Antrim also experienced serious divisions. In Belfast the division spread over to Scotland. But other places like Downpatrick became non-subscribing and experienced no division at all. Both Ballee and Clough remained subscribing, at this point, but joined those who opposed the expulsion of the non-subscribers.

The Presbytery of Antrim

In the background of all this was a developing pamphlet war and continuing arguments in the Synod and other church courts. A large number of pamphlets and books were produced on both sides of the argument but matters were eventually decided by votes in the Synod. Out voted by the orthodox side, which had the overwhelming support of the eldership, the non-subscribers were all placed in the newly created Presbytery of Antrim at the Synod of Dungannon held in June 1725. The following year the non-subscribers drew up a list of propositions which they presented to the Synod as “expedients for peace”. The non-subscribers were heard but the subscribing majority was not satisfied with their suggestions and the end result was the separation of the Presbytery of Antrim from the General Synod.

So this is how the first subscription controversy ended with the expulsion of the non-subscribers into the Presbytery of Antrim. It was a painful and intentionally final breach. And here things might have ended. But history would prove otherwise.